As part of a trans-Atlantic collaboration, researchers from the team of Kodi Ravichandran (VIB-UGent Center for Inflammation Research) and the University of Virginia School of Medicine (Charlottesville, Virginia, U.S.) have discovered how intestinal bacteria can exploit nutrients that are released from dying cells as fuel to establish intestinal infections.

Researchers have long been investigating two seemingly distinct fields of study: how certain bacteria colonize our intestinal tracts, and how our own cells die. But do those processes interact?

Kodi Ravichandran (VIB-UGent Center for Inflammation Research), says: “We have known for a few decades that the cell death process itself can indirectly influence bacterial infections by changing the body’s immune response. At the same time, we have also been studying how dying cells can communicate with their neighbors. What CJ (CJ Anderson, postdoctoral fellow) set out to ask was: if these dying cells are secreting factors that can be recognized and sensed by healthy neighboring cells, what is to stop other organisms like intestinal bacteria from recognizing these same molecules?”

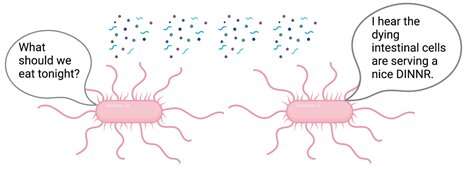

Using cell culture and healthy mouse tissue systems, the authors discovered that certain molecules are actively produced and shed by intestinal epithelial cells when they start to die. Interestingly, these molecules are directly sensed and used by intestinal bacteria such as Salmonella and E. coli.

The researchers showed that this relationship between dying cells and gut bacteria, which they term death-induced nutrient release (DINNR), takes place in several disease contexts. Intestinal bacteria can use cell death-related molecules to assist in colonization during food poisoning, inflammatory conditions (resembling Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) or Crohn’s Disease), and chemotherapy-induced mucositis. Gastrointestinal toxicity is one of the leading side effects in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy, and it can necessitate dose alterations that can reduce efficacy. Additionally, cancer patients receiving chemotherapy have a significantly greater risk of developing subsequent infections.

“This relationship between chemotherapy and bacterial infections was particularly interesting to us,” says Anderson. “Unlike foodborne infections or flareups of IBD or Crohn’s Disease where a patient does not know when he or she will be ‘under attack,” physicians know exactly when they are administering chemotherapeutic drugs to cancer patients. This means we have a therapeutic window where we can try to develop some sort of combination therapy to limit some of this fuel for bacteria.”

Source: Read Full Article