When learning to manipulate objects again after a stroke, a different grip strategy may be used as a stop gap, to compensate for any difficulties experienced during the healing period. When an area of the brain loses its supply of blood during a stroke, it is severely damaged, which affects specific functions controlled by that region.

The motor cortex is the area of the brain that communicates with muscles to produce movement—damage to this area can result in the loss of fine motor skills like grasping or picking up a small object. Regaining lost function is not simply a matter of practice but often requires time for damaged brain tissue to heal.

In a study published recently in Frontiers in Rehabilitation Sciences, researchers from the University of Tsukuba modeled how fine motor skills are regained after a stroke to better understand how the typical recovery profile reflects interactions between these factors.

“We used equations to model how skills are relearned and retained after a stroke. The equations treat skills almost as if they were resources being stockpiled, but with time constraints, like a bucket with a slow leak,” explains senior author, Professor Jun Izawa. “There is typically a point where performance suffers—almost as if the person’s injury has regressed.”

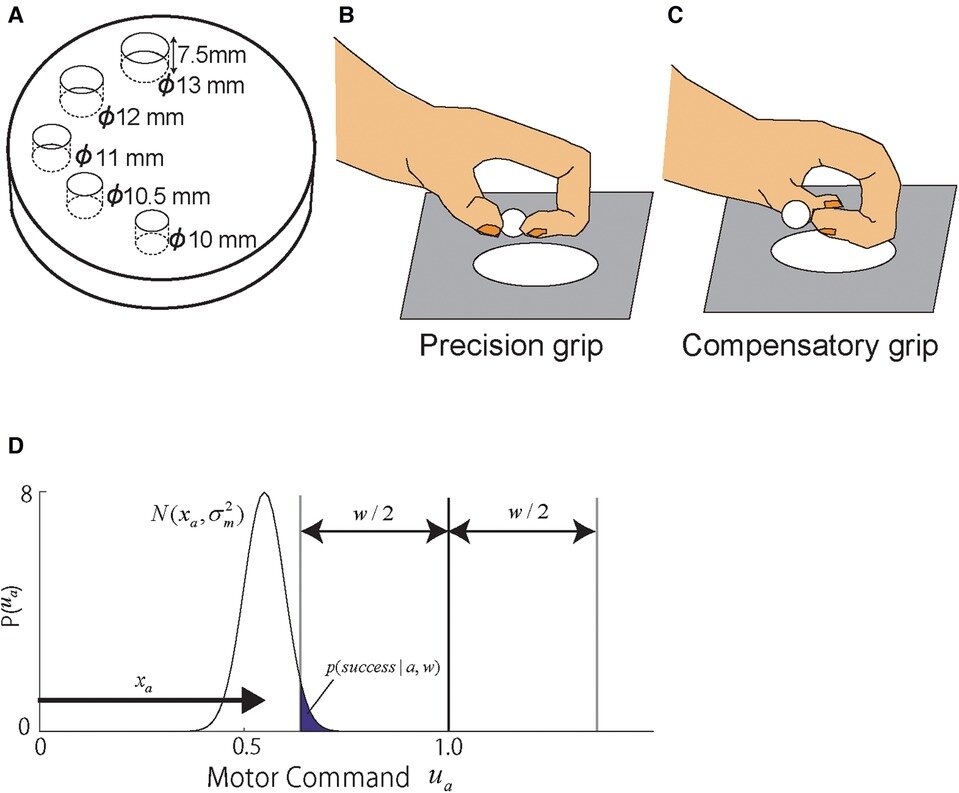

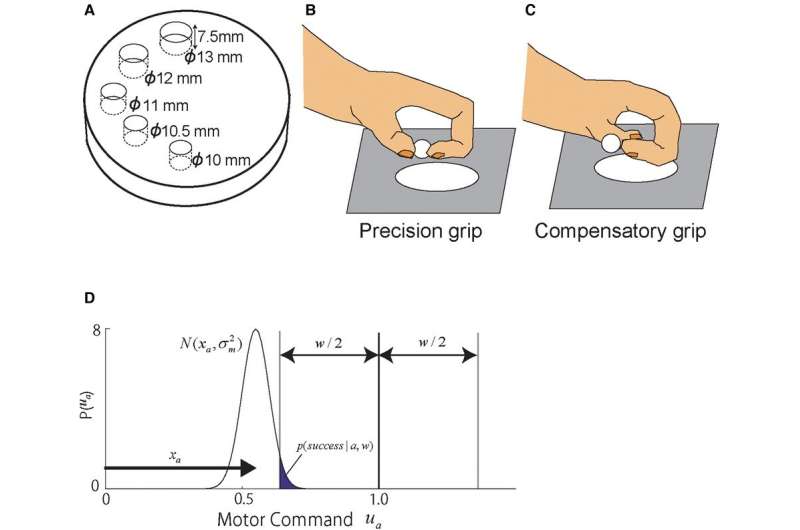

What causes a slowdown in the recovery process? There is a transition from compensatory skill to precision skill. Like in learning a new motor skill—for example, first learning to write letters—when relearning a skill after a stroke, the process is made up of a spontaneous part (in this case healing, rather than simply gaining the capacity with age and development) and a training-induced part (practice).

“Although the model was based on data from macaques, a similar recovery process occurs in people who experience a stroke,” says Professor Jun Izawa.

Source: Read Full Article