NEW YORK — Symptoms of early-stage cutaneous lymphoma (CL) often mimic nonmalignant skin diseases like psoriasis or eczema, leading to common misdiagnoses and missed opportunities for appropriate treatment.

While most patients with CL do not advance to late-stage, life-threatening disease, for the subset of patients who do progress, a lack of prognostic tools and the need for customized treatment make disease management challenging, according to Patrick M. Brunner, MD, MSc, associate professor of dermatology and director of the cutaneous lymphoma clinic at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York City.

“Cutaneous lymphoma is difficult to diagnose. Even when it is properly diagnosed, we do not have widespread use of biomarkers to predict if a patient will progress to a dangerous disease state,” Brunner said at the annual Mount Sinai Winter Symposium on Advances in Medical and Surgical Dermatology, where he presented an update on advances and areas of unmet need in cutaneous lymphomas.

Brunner said that an estimated 20%-30% of patients with CL progress to an advanced stage but cautioned that the 5-year survival rate in these patients can be as low as 30%. Although predictive tools to identify those who are at risk of disease progression are in their infancy, the development of such tools is crucial for improving patient outcomes.

Biomarker Studies

A team of researchers demonstrated that increased tumor clone frequency (TCF) as measured through high-throughput DNA sequencing of the T cell receptor β gene can predict the course of early-stage CL. In the longitudinal cohort study, patients who had a TCF greater than 25% were more likely to have aggressive disease. This test was shown to be especially predictive in patients with mycosis fungoides, the most common form of CL.

Not all patients are candidates for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (AHSCT) and the standard of care for managing CL still largely depends on disease state, Brunner said. Early-stage disease is often managed with skin-directed treatment that is relatively well tolerated. When the disease reaches a more advanced stage, with possible spread to blood, lymph nodes, or internal organs, treatment that can improve overall survival is more difficult to tolerate.

Two agents for treating relapsed or refractory (RR) CL have shown improved efficacy compared with older agents in clinical trials. Brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris) targets tumor cells that express the CD30-antigen. In the phase 3 ALCANZA study, patients with relapsed/refractory (RR) CL treated with the agent had a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 16.7 months compared with 3.5 months in patients treated with physician’s choice of therapy. Brunner noted that histological tests for CD30 expression are important to determine if this route of therapy is appropriate and likely to be effective.

In patients with CL that has spread to their blood, mogamulizumab (Poteligeo), a CC chemokine receptor type 4 (CCR4)-directed monoclonal antibody, is a promising treatment that targets CCR4, which is expressed in a majority of T-cell lymphomas. In the MAVORIC, open label randomized phase 3 trial, treatment with mogamulizumab extended median PFS to 7.7 months compared with 3.1 months in patients with RRCL treated with vorinostat (Zolinza).

Even with advances of new treatments, radiation and chemotherapy are necessary for some patients with RR CL that has spread beyond the skin. “Treating cutaneous lymphoma is an individualized process because it’s such a heterogeneous disease. It’s very important to tailor the treatment for the individual because not all treatments work for each patient,” explained Brunner.

He emphasized that, “other than stem cell transplantation, there’s no cure. Treatments are palliative, they’re just suppressing the disease. We definitely need better and safer treatments for our patients.”

Asked to comment on this topic, Raj Kumar Tuppal, MD, dermatologist at Lakeridge Health in Oshawa, Ontario, Canada, agreed with Brunner’s assessment of the challenges facing the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous lymphomas, particularly noting that despite advances in therapies and diagnostics, “treatment is often delayed due to misdiagnosis.”

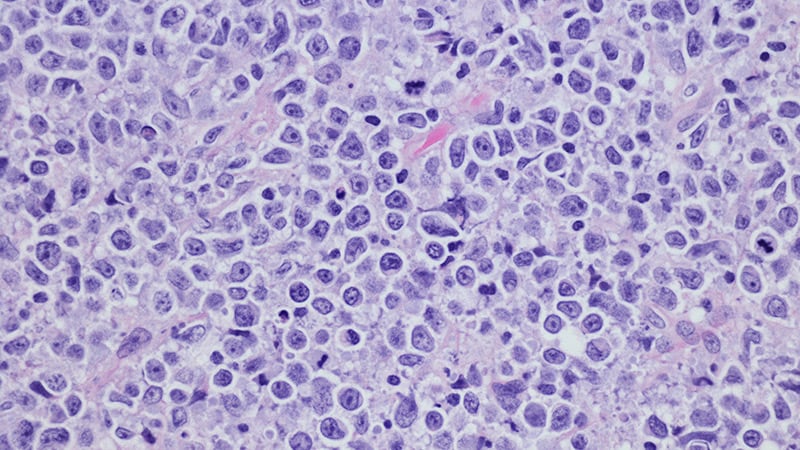

In his practice, when he sees something that might look like atopic dermatitis or psoriasis in an unusual place — like the abdomen or low back rather than in the elbows, knees, or scalp — he said, his “suspicions are raised that it could be a case of cutaneous lymphoma and that it might be time for a skin biopsy.” Looking at the lesion under the microscope could lead to treatment that would keep potentially malignant disease from spreading, he noted.

Brunner and Tuppal report no relevant financial relationships.

Myles Starr in a medical journalist based in New York City.

Source: Read Full Article