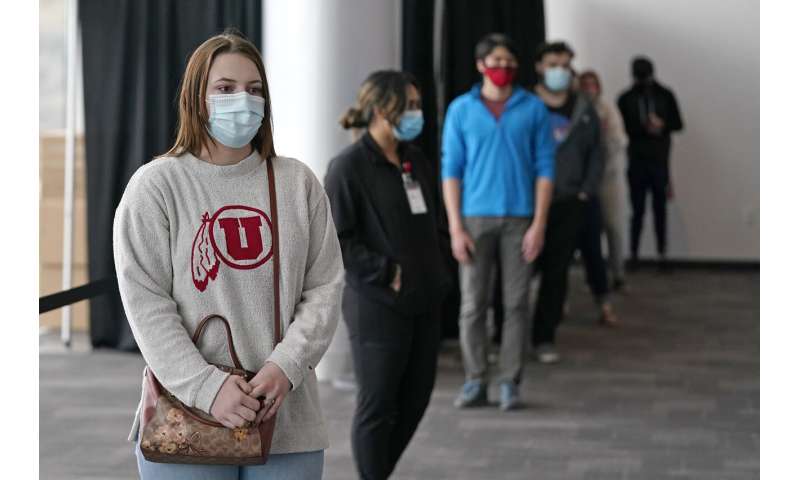

As college students prepare to go home for the holidays, some schools are quickly ramping up COVID-19 testing to try to keep infections from spreading further as the coronavirus surges across the U.S.

Thousands of cases have been connected to campuses since some colleges reopened this fall, forcing students to quarantine in dorms and shifting classes online. Now, many students are heading home for Thanksgiving, raising the risk of the virus spreading among family, friends and other travelers.

“The responsibility and the reach of the impact is not just to the student body anymore, it’s to those close contacts,” said Emily Rounds, a student who helps collect data on college testing plans nationwide for the announced a testing mandate after thousands of football fans, many without masks, stormed the field in South Bend, Indiana, and threw parties to celebrate a double-overtime upset over Clemson this month. Those who don’t complete the test can’t register for future classes.

Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, has a similar requirement, as does the public university system in New York.

The University of Pittsburgh, however, isn’t testing students before they leave, concerned that a single test could be unreliable and a negative result could give students a false sense of security.

“They are immediately going to get together with their high school friends and their families, and there is going to be a lot of outbreaks,” said Dr. John Williams, director of the school’s COVID-19 Medical Response Office.

Many schools, from the University of Texas at Austin to The Ohio State University, fall somewhere in between, encouraging but not mandating tests. The governors of seven Northeastern states, including New York, urged colleges in the region to provide testing for all students traveling home for Thanksgiving.

The few institutions that already regularly test students even without symptoms don’t have to change much.

The University of Illinois runs about 10,000 saliva tests a day, catching each student two or three times a week with a test developed by its own researchers. A required app reminds students to get tested and helps track those who test positive while they quarantine. It also includes a scan needed to get into campus buildings, only allowing in those who are up to date with their tests.

“People love it now. They feel, at the end of the day, this is the safest place in the world,” said Bill Jackson, who is executive director of the university’s Discovery Partners Institute and helps run the school’s pandemic response plan, which also includes mask-wearing and social distancing.

For other schools, finding and paying for tests has been a major hurdle amid virus-related economic upheaval, said Rounds, the student data collector.

“It can’t just be this narrative of blaming students and administrations … I really think, at this point, we need to look to state governments and the federal government to have some responsibility,” she said. “So many cases of COVID in the United States are coming from higher ed institutions—that should be a point of target for interventions.”

Governments are getting involved in some places, like North Carolina, where the state is providing tests to schools ahead of the holiday break, and Utah, where the governor has mandated weekly testing starting in January and the state is helping with rapid-response test kits.

At the University of St. Thomas in Saint Paul, Minnesota, the state helped source 3,500 tests before Thanksgiving break. Previously, only students with symptoms and some in close contact with a person with COVID-19 were able to get tested.

But now there’s a shortage of medical personnel to administer the extra tests. That means faculty like journalism professor Mark Neuzil have stepped in as the university began mass testing Wednesday, administering about 100 tests an hour, he said.

“The state provides you with the tests and then says, ‘Good luck,’ because there’s not enough medical personnel to go around,” Neuzil said. “We, of course, have health services and we have nurses, but they’re working like dogs and there’s not enough of them.”

For students, testing availability can be a relief.

Ben Ferney, a 24-year-old communications major at northern Utah’s Weber State University, recently took a rapid-response test at a folding table set up in a ballroom at the student union. He caught the virus this summer, but because it’s still unclear how long immunity lasts, he wants to ensure he doesn’t get it again.

“I don’t think I’ve ever been that sick in my life,” Ferney said. He said he apparently spread the virus to his parents and two siblings before he even knew he was sick.

Source: Read Full Article