Despite the heightened poverty and unemployment seen when the COVID-19 pandemic got underway, many low-income U.S. children did not experience a decline in their emotional and mental health, we found in a new study.

We looked specifically at kids whose families were participating in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program—commonly known as SNAP—the government program that helps low-income Americans afford food.

The government began to boost SNAP benefits in early 2020 to help offset pandemic-driven food insecurity for participating families, which now number around 41 million.

As a result, families got an extra US$95 or more per month for groceries to replace the meals children were missing at schools that had closed. Some eligibility rules were loosened to expand the program’s reach, and for the first time, people could buy groceries online with their SNAP benefits.

To learn whether these extra benefits affected children’s mental and emotional health, we analyzed five years of data collected by the National Survey of Children’s Health on 30,748 low-income families with children aged 6 to 17 years. The data, which included both families who were and were not getting SNAP benefits, covered the four years prior to the pandemic, as well as 2020.

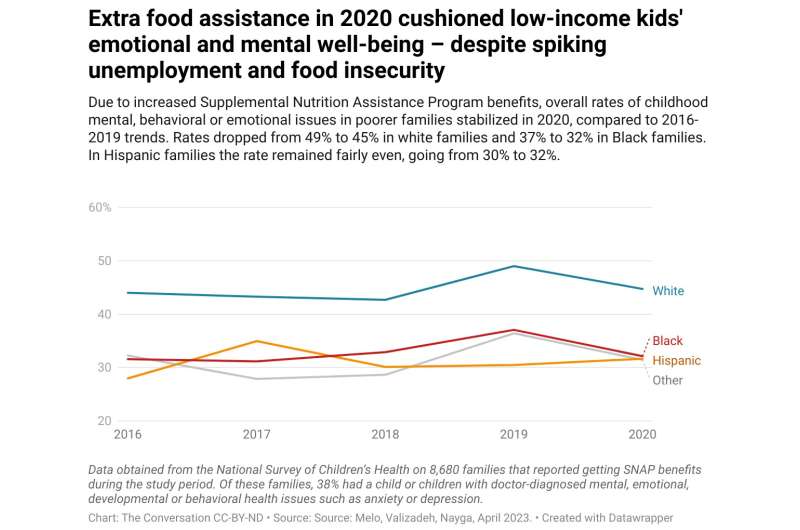

Among the 8,680 families getting SNAP benefits during this period, 38% had at least one child with problems such as doctor-diagnosed mental, emotional, developmental or behavioral health issues—including anxiety and depression.

To assess whether the temporarily expanded benefits had an impact on these children, we conducted a “difference in differences” analysis: We compared data regarding children whose families enrolled in the SNAP program over time with children whose families didn’t get those benefits. In addition, we considered the potential influence of several factors that could play a role, such as parents’ mental health.

We found that children in families getting SNAP benefits in 2020 did not generally experience any change in their mental or emotional health compared to prior years, despite the heavy stress of the pandemic.

Typically, low-income children are more at risk of developing mental health or emotional problems, compared with high-income children. Our study adds to earlier evidence that SNAP benefits can lower that risk by reducing psychological distress and improving food security.

While 2020’s extra SNAP benefits protected children’s mental and emotional health, they did not improve it. This suggests that actually reducing food insecurity for low-income families would have required additional steps.

In March 2023, the federal government ended the pandemic-era SNAP expansions in 35 states and territories that hadn’t yet rolled them back. With inflation driving the cost of groceries up 11.4% in 2022, we believe that losing these benefits threatens the well-being of millions of families.

We are now studying the effects of pandemic-related changes to the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children, better known as WIC.

We are looking at, for example, how expanding WIC benefits to cover canned, frozen and dried fruits and vegetables in addition to fresh produce has affected the low-income families’ purchasing behavior. Our team for this research also includes public health and nutrition scholars Alexandra MacMillan Uribe and Elizabeth Racine.

When we did our study, data from the years after 2020 wasn’t yet available, so we couldn’t investigate the potential impact of subsequent pandemic-related changes to SNAP benefits. Notably, in 2021, the federal government increased maximum benefit levels by 15% and extended the extra $95 or more in monthly food assistance for the lowest-income households.

Provided by

The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Source: Read Full Article