By targeting an enzyme that plays a key role in head and neck cancer cells, researchers from the UCLA School of Dentistry were able to significantly slow the growth and spread of tumors in mice and enhance the effectiveness of an immunotherapy to which these types of cancers often become resistant.

Their findings, published online in the journal Molecular Cell, could help researchers develop more refined approaches to combatting highly invasive head and neck squamous cell cancers, which primarily affect the mouth, nose and throat.

Immunotherapy, which is used as a clinical treatment for various cancers, harnesses the body’s natural defenses to combat disease. Yet some cancers, including head and neck squamous cell carcinomas, don’t respond as well to the therapy as others do. The prognosis for these head and neck cancers is poor, with a high five-year mortality rate, and there is an urgent need for effective treatments.

The UCLA research team, led by distinguished professor Dr. Cun-Yu Wang, chair of oral biology at the dentistry school, demonstrated that by targeting a vulnerability in the cellular process of tumor duplication and immunity, they could affect tumor cells’ response to immunotherapy.

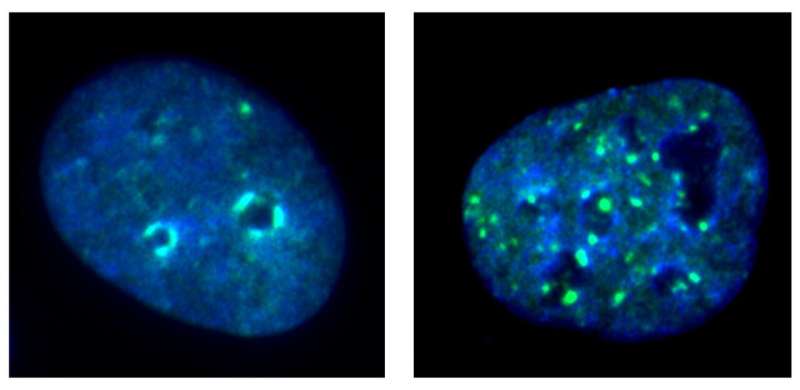

The enzyme they focused on, KDM4A, is what is known as an epigenetic factor—a molecule that regulates gene expression, silencing some genes in cells and activating others. In squamous cell head and neck cancers, overexpression of KDM4A promotes gene expression associated with cancer cell replication and spread.

It is well known that tumor cells can spread undetected by the immune system and, without surveillance, can metastasize to lymph nodes or other parts of the body. In this instance, tumor cells that develop in the epithelial layer that lines the structures of the head and neck can turn into head and neck squamous cell carcinoma when unchecked.

Cancer cell replication occurs through the abnormal spread and activation of signaling pathways for cancer cells, and the researchers asked the question: If we can disrupt these processes and identify a vulnerability, can we change the body’s response to fighting cancer cells and its response to outside immunotherapy?

“We know that the KDM4A gene plays a critical role in cancer cell replication and spread, so we focused our study on removing this gene to see if we would get an opposite response,” said Wang, the study’s corresponding author and a member of the UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center.

By removing the KDM4A gene in their mouse models, the researchers witnessed a notable decrease in squamous cell carcinomas and far less metastasis of cancer to the lymph nodes—a precursor to the spread of the disease throughout the body. Surprisingly, they also discovered that the KDM4A’s removal also led to the recruitment and activation of the body’s infection-fighting T cells, which killed cancer cells and stimulated inherent tumor immunity.

They then sought to uncover why the squamous carcinoma cells had such a poor response to immunotherapy treatment. In another set of mouse models, they again removed KDM4A and introduced a PD-1 blockade, which signals immunotherapy drugs to attack cancer cells. The combination of immunotherapy and KDM4A removal further decreased squamous cell cancer growth and lymph node metastasis.

Next, the researchers tested whether a small-molecule inhibitor of KDM4A could improve the efficacy of the original PD-1 blockade-based immunotherapy. They found that the inhibitor also significantly helped remove cancer stem cells, which are associated with cancer relapse.

The findings hold promise for the development of more specific inhibitors for KDM4A and more effective cancer immunotherapies.

Source: Read Full Article