Poop can be a tricky subject: We all do it, and excreting waste is critical to life. But the rules of etiquette ensure we’re rarely brave enough to speak openly about it. The feces—or stools—that we produce, however, can provide a valuable real-time window into the health of your large bowel (or colon) and gastrointestinal tract. So let’s put those rules aside for now.

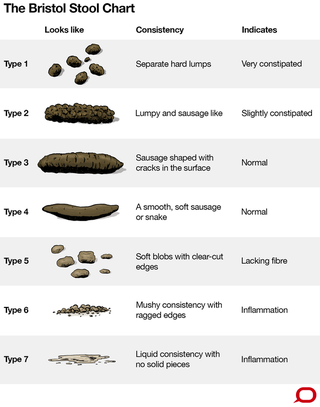

Scientists research many odd topics, and stool form is no exception. In 1998, Stephen Lewis and Ken Heaten from the University of Bristol developed a seven-point stool form scale, ranging from constipation (type 1) to diarrhea (type 7).

Today, the Bristol Stool Chart allows people with gastrointestinal symptoms to clearly describe to their doctor what they are seeing in the toilet without having to provide samples.

For most of us, the form of stool we excrete can vary widely depending, in part, on what we’ve been doing. A period of dehydration, perhaps associated with a day of sustained exercise, or the delaying of a bowel movement, may be followed by a drier stool form than normal. Conversely, an unusually spicy meal might be followed by a bowel movement with a looser stool.

What should your poop look like?

Ideally, stools should be easy to pass without straining and without any intense sense of urgency. On the Bristol Stool Chart, these are types 3, 4, and 5: sausage-like with some cracks in the surface, up to 2 to 3 cm in diameter; longer sausage or snake-like with a smooth consistency, similar to that of toothpaste with a typical diameter of 1 to 2 cm; or soft blobs with clear cut edges.

While arguably easier to clean up, the drier stool forms (types 1 and 2) tend to compact into large stool that can apply long term pressure to and abrade the lining of the large bowel. During a bowel movement, dry stools may distend the anal canal beyond its normal aperture. This may require straining—and pain—to pass.

Straining to pass dry stools increases the risk of laceration of the anus, hemorrhoids, prolapse, and the condition diverticulosis. That’s when pouches form on the wall of the large bowel due to over-distension, which can become sites for infection or inflammation.

Watery stool forms may be associated with gut infections—for instance, with a gut parasite like Giardia, or an inflammatory disorder such as Crohn’s disease.

As a rule, softer but not watery stool forms are best. Any change of bowel habit that leads to the sustained production of drier stools and a sense of incomplete emptying—or watery stools and a feeling of urgency—should be discussed with your doctor.

How does your hydration affect your poop?

Even to the casual toilet bowl observers among us, the most obvious differentiating factor between stool forms is their water content. The large bowel is an amazing recycling and repurposing center for the body. Water recycling is one of its key functions.

Every day, our bodies invest around two gallons of fluids into the digestion of food, including around six cups of saliva, more than half a gallon of stomach secretions, and more than 3 cups of bile. But clearly we don’t defecate anywhere near this volume.

The longer it takes for digested food to pass through the large bowel, the more water gets reclaimed and the drier the stool becomes. So factors affecting the transit rate of food through our gastrointestinal tract will have a significant influence on stool form. Antibiotics, pain killers (particularly opiate-containing drugs such as Endone but also more common pain-killers containing codeine) as well as physical inactivity all reduce how well the gut contracts. This slows the passage of food through the large bowel, which can lead to constipation.

How does your diet affect your poop?

Our diets also play a significant role in stool form and health. Observational studies performed in south and eastern Africa in the 1970s and 80s compared the gastrointestinal health of Caucasians eating a Western-style diet and native Africans living a traditional lifestyle. The researchers found drier stool forms and constipation were more common in people who ate Western-style diets.

This was associated with increased incidence of bowel cancer, inflammatory bowel diseases, as well as other chronic diseases. The results were attributed to differing levels of fiber in the diets of these two populations and these conclusions have been clearly confirmed for bowel cancer in numerous studies.

Fiber impacts how long it takes to poop, the shape of your stool, and your stool health in two ways. First, when a healthy, well-hydrated person eats fibrous foods such as wheat bran with lots of roughage, the food takes up water and swells. This increases the volume of the stool—softening it, and helping it pass easier. At the same time, it dilutes and more rapidly clears any toxins that may have been ingested with the food.

More potent components of dietary fiber also exist: fermentable carbohydrates such resistant starch (a form of starch that is not digested in the small intestine), beta glucans and fructo-oligosaccharides, which are commonly found in whole grains, legumes, pulses, fruit and vegetables. These are a key nutritional source for the trillions of bacteria that inhabit the large bowel (the gut microbiota).

Key waste products of this bacterial feast—short-chain fatty acids—are like gold to our bodies. One of these short-chain fatty acids, butyrate (which is also the food acid that gives parmesan cheese its aroma), reduces the time it takes people to poop by strengthening the contraction of muscles lining the large bowel.

On the way, these short-chain fatty acids strengthen, grow, and repair the cell layers that line the large bowel. They destroy cancerous cells, reduce inflammation and pain in the gut, and enhance satiety. But one gastronomic casualty of the Westernization of our diets has been fiber. A typical Westerner may consume as little as 12-15 grams of fiber per day.

So clearly, we have a ways to go. There is a caveat, however: If you have gastrointestinal symptoms—such as an upset stomach, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea—fiber may not always help. You may need to carefully consider the type of fiber you consume, with the help of your doctor.

The roughage component of some fiber sources may exacerbate symptoms for people with diverticular disease, for instance. Symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome may be worsened by fiber sources rich in fermentable fructose oligo, di or mono saccharides and polyols (FODMAP). This includes onions, garlic, apples, pears, milk, legumes, some breads and pasta, and cashews.

For most of us, though, more fiber in our diets should reduce the time it takes to poop, soften our stools, make bowel movements more comfortable, and improve our overall bowel health.

Trevor Lockett is the group leader of personalized health at The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, Australia’s national science agency.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Source: Read Full Article