Of the several hundred thousand health apps available globally in major app stores, most lack high-level evidence on their outcomes, according to a recent study in Nature Digital Medicine.

Natasha Singer

Flo and Clue, two popular period-tracking apps, recently introduced health tools that evaluate a woman’s risk for the hormonal imbalance known as polycystic ovary syndrome.

In September alone, more than 6,36,000 women completed the Flo health assessments, said the app’s developer, Flo Health. The app then recommended that 2,40,000 of those women, or about 38 per cent, ask their doctors about the hormonal disorder. (BioWink, the developer of Clue, declined to provide similar usage statistics.)

But what many women who used the Flo and Clue health tools may not have known is that the apps did not conduct high-level clinical studies to determine the accuracy of their health risk assessments or the potential for unintended consequences such as overdiagnosis. As a result, some experts said, the new tools could lead some women to be labeled with a hormonal imbalance they did not have or that may have no significant repercussions for their health.

“You could be making a lot of people concerned they have a problem that they don’t know will have absolutely no clinical consequences for them,” said Dr. Jennifer Doust, a professor of clinical epidemiology at Bond University in Queensland, Australia, who has studied polycystic ovary syndrome, which is known as PCOS.

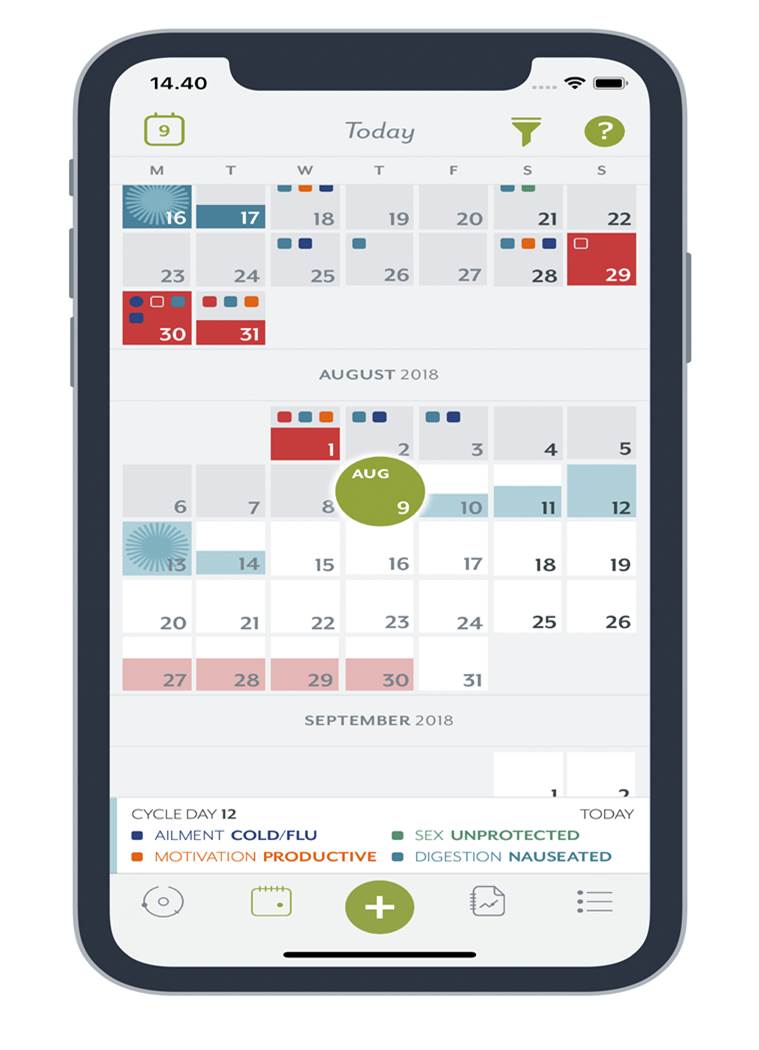

Flo’s and Clue’s health assessments are part of a broader shift in digital medicine. Health tracking apps have for years helped people collect and chart data on their heart rates, moods, sleep patterns and menstrual cycles. But now some of these apps are going further by using that data to predict an individual’s risk for problems like heart conditions. In other words, they are moving from simply quantifying consumers’ health data to medicalizing it.

While some of the apps’ new evaluation tools may be useful and helpful, determining whether they are accurate can be difficult. Of the several hundred thousand health apps available globally in major app stores, most lack high-level evidence on their outcomes, according to a recent study in Nature Digital Medicine. And as long as consumer health apps make vague health promises — like improved well-being — and do not claim to diagnose or treat a disease, they are not typically required to submit effectiveness evidence for vetting by the Food and Drug Administration.

“It’s certainly become confusing as a consumer if you go onto these app marketplaces and these apps are making claims about helping you learn about mental health, PCOS, heart disease, diabetes,” said Dr. John Torous, director of the digital psychiatry division at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, one of the authors of the Nature study. “Do we know this helps or it doesn’t help?”

Flo, which has more than 30 million active monthly users, and Clue, with more than 12 million, have good intentions. Their developers each said they had worked with medical experts to develop the assessments and had based them on international medical guidelines for identifying PCOS. The apps also include prominent disclaimers saying that their assessments for PCOS should not be construed as diagnoses.

But in a recent news release, Flo described its service as a “digital, pre-diagnostic tool” to help women “discover if they have PCOS and also bring peace of mind to others who may suspect they have it.” Clue said its “probabilistic statistical model” for the hormonal imbalance offered a “smart assessment that can be shared with doctors.”

One woman, a product manager in the San Francisco Bay Area interviewed by The New York Times who used Flo, said it gave her more information about PCOS than her doctor had. But Sasha O’Marra, a copywriter in Toronto who tried a beta version of Flo’s health risk feature in July, said she found the assessment irresponsible.

The app said O’Marra’s symptoms — acne and menstrual cycle changes — “may indicate a hormonal imbalance which is probably a manifestation of PCOS.” She took the company to task on Twitter, explaining that her period had changed because she had just changed birth control pills.

“It’s very concerning to me,” O’Marra said in an interview. “Telling people they might have something like PCOS without understanding the context behind their symptoms is a slippery slope.”

The company responded on Twitter: “Here at Flo, we use medically approved algorithms.” It explained that its algorithm considered multiple factors. “If some symptoms match, we encourage a user to visit a doctor just to make sure that everything is fine.”

In an email, Flo said the app includes a disclaimer that its PCOS assessment is not designed for women who use long-term birth control methods.

Polycystic ovary syndrome is a prevalent health problem among women of childbearing age. Its symptoms can include elevated testosterone levels, irregular periods and abnormal facial hair growth. The syndrome can make conceiving without fertility treatments more difficult for some women.

The apps’ PCOS risk assessment tools are easy to use. They ask women a series of questions about possible symptoms, adapting to certain answers with follow-up questions. After people complete the questionnaires, the apps tell them whether their symptoms seem suggestive of the hormonal imbalance and may recommend they ask their doctors about it.

Professional medical groups disagree over which symptoms are needed to identify the hormonal imbalance — and whether it is overdiagnosed or underdiagnosed. One 2017 study of about 1,400 women who eventually received a PCOS diagnosis, for instance, reported that about one-third of them consulted at least three physicians before the syndrome was identified.

Women who have been misdiagnosed with PCOS said the experience could be jarring.

“I was really stressed during that time because I really thought maybe I wasn’t going to be able to have kids,” said Sabrina Wisbiski, a human resources coordinator in the Detroit area, who said she was erroneously told by an endocrinologist a few years ago that she had the disorder. She said she later discovered that she had a different hormonal problem set off by intensive bodybuilding.

“I feel like a lot of doctors did not have the right knowledge or experience with women who lose their periods from overtraining and they turned to PCOS as a blanket diagnosis,” she said.

Clue and Flo each said their assessments did not make definitive health judgments. If the apps detect a risk, Flo tells its users that their symptoms “could be a manifestation of PCOS,” while Clue tells its users that PCOS is “a possible cause” of their irregular periods.

Clue also said it had tested its risk models for the hormonal disorder on nine hypothetical patients who were assigned different symptoms. The prediction models incorrectly detected PCOS in one to two of the virtual patients — and also typically assigned the virtual test subjects a risk score more than 15 percentage points higher than a physician did.

“We err on the side of caution,” said Daniel Thomas, Clue’s head of data science. “Even if we think it’s more likely that they don’t have PCOS than having PCOS, but it’s one of these gray zone cases, we would also still ask them to see the doctor.”

Torous, who has published studies on the evidence supporting health apps, said the validation method could skew Clue’s health risk assessments.

“If you’re training a model on virtual patients, the model learns how to treat virtual patients,” he said. “But a virtual patient is not you or me or a real person.”

Flo offered its PCOS assessment tool to all of its users last month, but it has now limited it to women with irregular periods who have logged at least six menstrual cycles on the app. Kamila Staryga, vice president of product at Flo Health, said the system aims to make more women aware of PCOS and help them “weed out whether a condition is something that they should call the doctor” about.

But the Flo app — unlike Clue — did not ask about eating disorders or workout routines, factors that could explain irregular periods. Flo said its assessment did not ask users about them because international medical guidelines for identifying PCOS did not include those criteria. The Flo app also frames certain questions in ways that could tilt women’s responses toward the hormonal disorder.

“Irregular periods may be a symptom. Do your periods always start in the same timeframe?” one question on the Flo app said. Another said: “Plenty of acne in more than six months that usual skincare fails to cure could mean a hormonal imbalance caused by PCOS. Do you experience acne?”

“It’s kind of suggesting the answer, isn’t it?” said Doust of Bond University. “If you were in any way thinking in your head already, ‘Oh, I must have PCOS,’ then it’s kind of suggesting what you have to say to get that answer.”

Source: Read Full Article