Pandemic-induced public health measures, such as social distancing and stay-at-home orders, while successful in decreasing the transmission of COVID-19, could exacerbate pre-existing mental health challenges, including loneliness, one of the major public health concerns in pre-pandemic times.

A new nationwide study published in the Journal of Affective Disorders estimated that in Canada, 34.7% percent of the population, or just over one out of three Canadians, experienced severe loneliness in the second wave of COVID-19 infections, in January 2021. Moreover, this estimate of Canadian loneliness was substantially higher than statistics (14%–27%) reported elsewhere in the world during the pandemic.

“This concerning magnitude implies that during the pandemic lockdown, severe loneliness was ubiquitous in Canada,” says the sole author, Dr. Lamson Lin Shen, an assistant professor in City University of Hong Kong’s Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, who conducting the research while finishing his Ph.D. degree at the University of Toronto’s Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work.

“This is probably due to the disruption in daily social activities, which normally help people cope with stress, as well as the intense social isolation caused by the lockdown measures implemented in many provinces of Canada.”

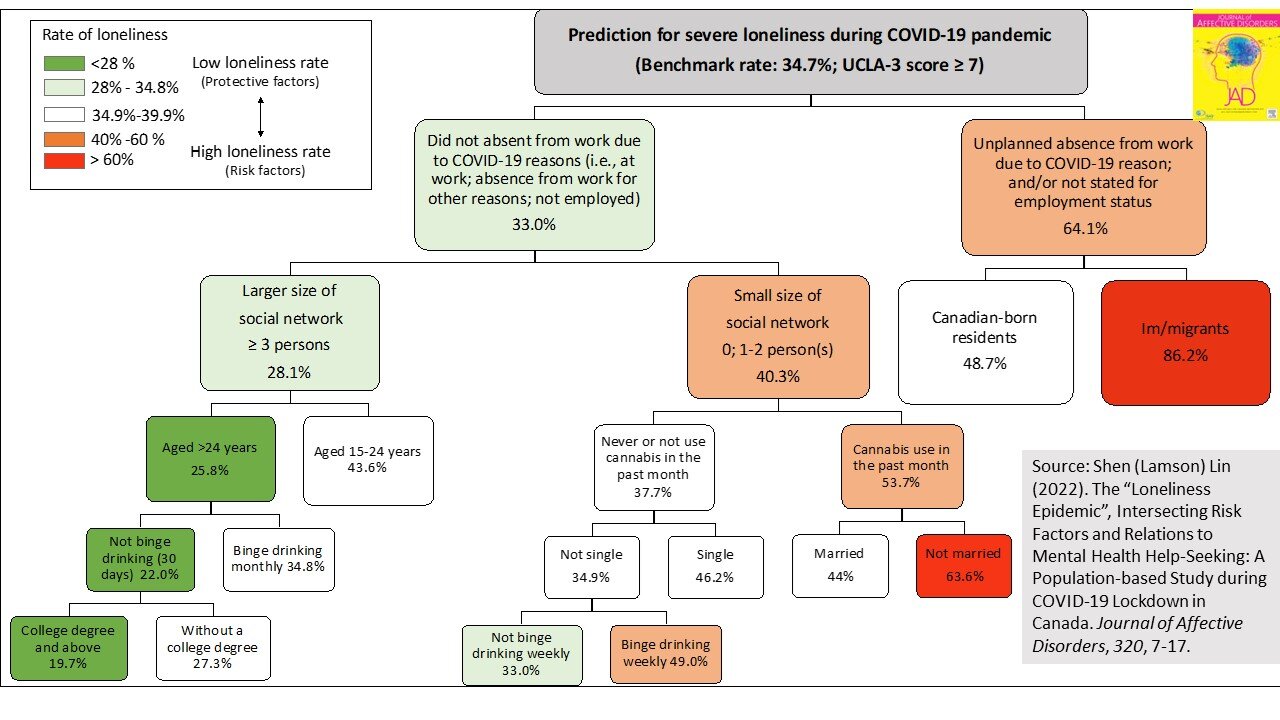

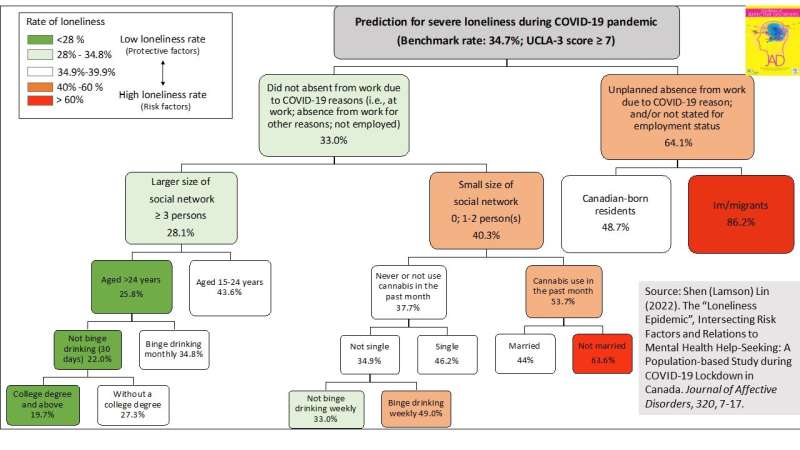

Based on the population-representative data from the Canadian Perspective Survey Series, collected from 25 to 31 January 2021 (during the larger second wave of the pandemic in Canada), the study adopted a machine-learning approach, Classification and Regression Tree (CART) modeling, to discover population patterns of loneliness symptoms measured by the standardized UCLA 3-item loneliness scale among 3,772 participants.

The CART algorithm found that migrants who experienced pandemic-triggered job insecurity, such as business closures, layoffs or absence from work due to COVID-19 diagnosis, were the among the groups most at risk of severe loneliness.

“It is not surprising that immigrants were particularly vulnerable to isolation and loneliness in pre-pandemic times, because they were in a new environment, where they may have faced a variety of post-migration stressors, such as language obstacles, limited social networks, and a diminished sense of community belonging,” says Dr. Lin. “What struck me the most is that my study discovered the double jeopardy of immigrant status and an unstable job situation during the COVID period.”

According Dr. Lin’s findings, individuals who experienced job instability during the pandemic had double the odds of experiencing severe loneliness compared to people who were securely employed, after controlling for confounding variables, including sociodemographic factors. Among those experiencing insecure employment, the prevalence of loneliness was substantially higher among immigrant population than among Canadian-born residents (86.2 % vs. 48.7 %).

“The COVID-19 pandemic indeed amplified immigrants’ susceptibility to loneliness,” says Dr. Lin. “This may be due to the fact that many migrants to Canada are over-represented in low-paid, low-skilled, unstable jobs, such as retail positions, cleaners, or cashiers, that require extensive interaction with the public, so they are at greater occupational risk of COVID-19 infection and consequential employment insecurity.”

In addition, Dr. Lin’s research identified several at-risk groups of loneliness that are consistent in ordinary times, including youth and adolescents, women, people with a low educational background, people living alone, people with a limited social circle (less than three persons), binge drinkers, and past-month cannabis users.

His study also demonstrated that, compared to Canadians who did not experience loneliness, severely lonely individuals in Canada were 1.7 times more likely to seek treatment from mental health professionals, 1.5 times more likely to seek informal support for mental health concerns, and 1.8 times more likely to have unmet mental health needs.

“My findings further shed light on the importance of building an equitable mental health care system in the pandemic response and recovery in Canada and other immigrant-receiving countries of the world,” said Dr. Lin.

“Primary care providers and mental health clinicians should assess loneliness symptoms in their routine patient examinations. At the community level, social care organizations should develop early prevention and intervention programs targeting high-risk groups with a greater burden of loneliness, especially for immigrant and marginalized populations.”

More information:

Shen (Lamson) Lin, The “loneliness epidemic”, intersecting risk factors and relations to mental health help-seeking: A population-based study during COVID-19 lockdown in Canada, Journal of Affective Disorders (2022). DOI: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.08.131

Journal information:

Journal of Affective Disorders

Source: Read Full Article