Could we temporarily increase brain plasticity in adults to decrease fear and anxiety responses in people who have experienced trauma? CHU Sainte-Justine Neuroscientist Graziella Di Cristo and her team were determined to find out. In a new study on mice, she was able to control fear responses by inducing desensitization to fear memories simultaneously with a temporary increase in brain malleability through control of gene activation. This is an exciting breakthrough for the treatment of people with symptoms related to post-traumatic stress.

The results of this study were published on May 2, 2023, in the journal Molecular Psychiatry.

Fear arising from a traumatic event can lead to persistent memories that induce phobias, anxiety and even post-traumatic stress disorder. In severe cases, gradual desensitization therapies supervised by a therapist can be used to dissociate fear responses from memories. Previous studies have shown that this type of therapy is more effective with children, whose more malleable brains facilitate the creation of new memories and the dissociation of fear responses.

Graziella Di Cristo’s lab investigates GABAergic interneurons, inhibitory cells that slow down brain activity. Among these interneurons, cells expressing the protein parvalbumin control neuronal network and circuit dynamics in the brain, including the parts that modulate thoughts and fears.

A gene and a protein associated with brain plasticity

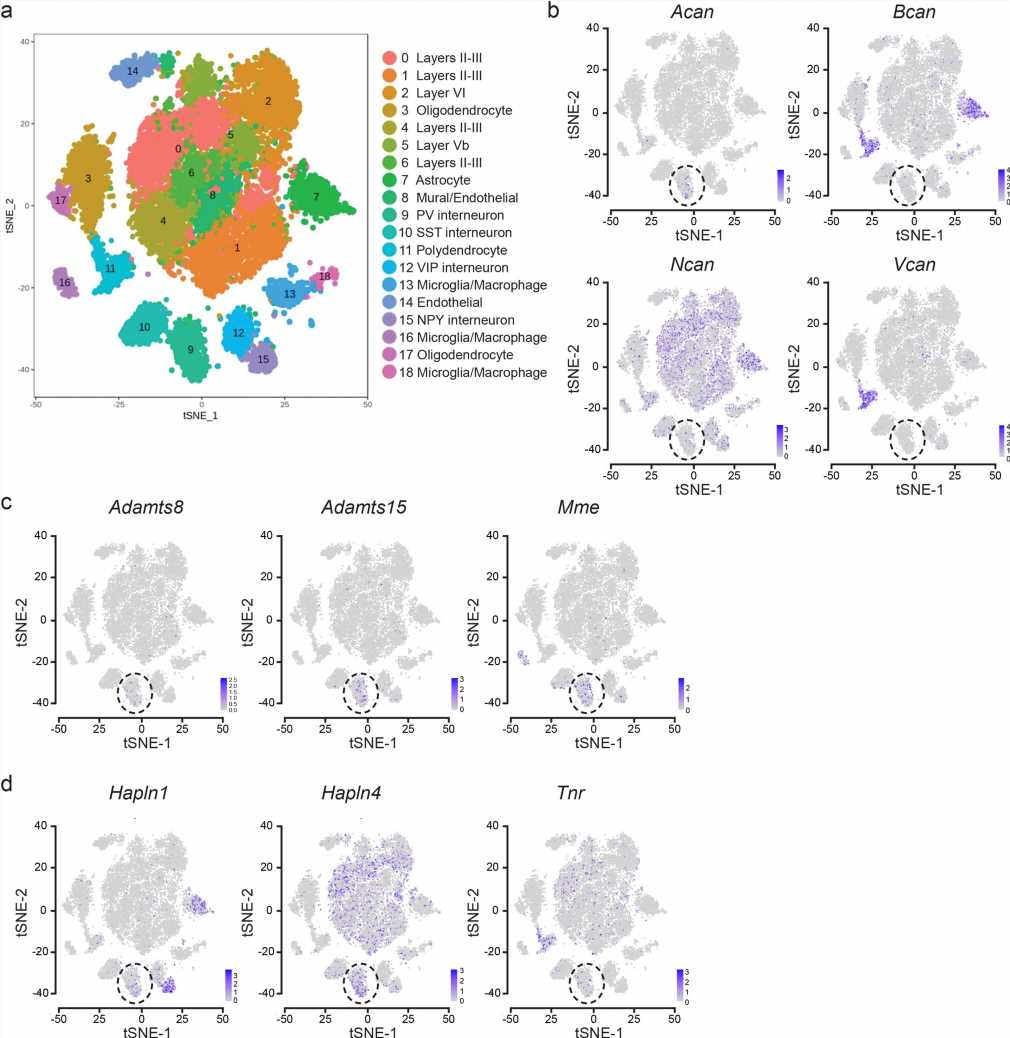

In children’s brains, the parvalbumin cell network is more malleable due to the lower presence of the protein Aggrecan. “This protein surrounds and solidifies parvalbumin cells during the maturation process of the brain through a structure called perineuronal nets, making them less malleable,” explained Graziella Di Cristo, who is also a full professor in the Department of Neuroscience at Université de Montréal’s Faculty of Medicine.

“In collaboration with researcher Graciela Piñeyro and Dr. Gregor U. Andelfinger’s research teams, we discovered that the protein Aggrecan, encoded by the Acan gene, was specifically expressed in parvalbumin-positive interneurons. We had found a possible target to destabilize the solidification of perineuronal nets, without affecting other neuronal populations, by decreasing the expression of the Acan gene,” explained Marisol Lavertu-Jolin, Ph.D. student at the time and first author of the study.

How to control the production of Aggrecan in the brain

With a scientific collaboration of a research team based in India, the CHU Sainte-Justine team has developed a molecule called siARN which not only has the property to inhibit a gene, but also to cross the blood-brain barrier through the bloodstream.

“We had to verify that the siARN, injected in the blood, specifically inhibited the Acan gene and therefore increased malleability of the brain,” explained Graziella Di Cristo. “This is key to promoting the creation of new memories and allowing the desensitization of fear-inducing memories to be effective in the long term.”

The experiment was a success. The temporary increase in brain plasticity allowed the formation of new memories in adult mice and the decrease of fear responses to traumatic events.

This groundbreaking study paves the way for potential clinical research in adults with post-traumatic stress disorder to improve the long-term success of exposure therapies.

More information:

Marisol Lavertu-Jolin et al, Acan downregulation in parvalbumin GABAergic cells reduces spontaneous recovery of fear memories, Molecular Psychiatry (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41380-023-02085-0

Journal information:

Molecular Psychiatry

Source: Read Full Article