While I was growing up, I acted out my dreams all the time, making me a hit at slumber parties. I remember my cousin would say, “It’s so fun to spend the night with you because you’re always moving around and talking.”

The thing was, I wouldn’t reenact my dreams while I was awake. I would actually act them out while I was asleep. In one of my earliest memories of sleep-acting, I was about 9 years old, and my mom found me wandering around our front yard. When she asked me what I was doing, I apparently told her I was looking for a sheet of paper. In my dream, I needed it to cross a bridge.

While my mom was concerned about my sleep-acting, my younger sister (who shared a bed with me) found it funny and novel. In my teenage years, I had a job at Walmart and often popped up in bed in the middle of the night talking to customers and scanning imaginary items. She’d wake me up and laugh and tell me to go back to sleep.

As the years went on, my family members got used to finding me walking around at night. They’d just tell me I was dreaming and lead me back to bed. Since I always lived with other people—my parents and sisters, roommates, husband—there was always somebody there to look out for me.

In 2009, that changed when my husband began working night shifts. For the first time, I was home alone at bedtime.

My sleep-acting seemed to get worse when I was stressed out, and I’d dream about all sorts of weird things. One night, I woke up holding the front door open to welcome students into school (I’m an art teacher IRL). Another night, I woke up clawing at the wall because I was trying to rescue kittens in a dream.

What finally led me to seek treatment, though, was when I had a dream that the Salvation Army was coming to our house to pick up some donations. It was raining in my dream—and in real life—and I woke up bent out of our second-story back window with the rain hitting me. I thought, Oh my gosh. I could have fallen out of that window! I was really scared.

That experience made me realize my sleep-acting was happening more often than I’d thought. When I was alone, I wasn’t safe.

After the window incident, I was finally compelled to start researching my sleep-acting problem.

I went online to look up my symptoms and came across Washington University’s Sleep Medicine Center in Brentwood, Missouri. I immediately contacted their sleep clinic to schedule an appointment.

After a questionnaire, physical exam, and neurological exam, the sleep doctor suspected that I had a parasomnia (a sleep disorder that causes abnormal behavior while you’re falling asleep, sleeping, or waking up, like sleepwalking or having sleep terrors). But to figure out exactly what was going on with me, I’d have to go back for a nocturnal sleep study, they told me.

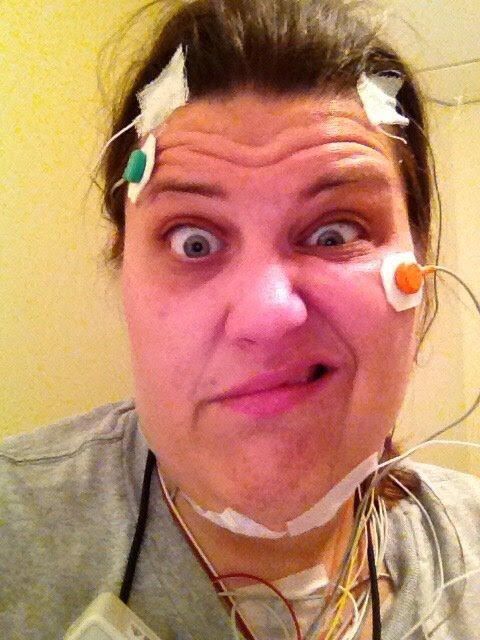

The night of the sleep study, sensors were placed all over my body for a polysomnogram test which would monitor my heart, breathing, brain activity, and arm and leg movements. I was also videotaped.

When I woke up, I was worried—I hadn’t acted out any dreams. How could they know what was going on if I didn’t do anything? What I didn’t know was that the sensors had been able to pick up that something strange was happening to me at night, even though I didn’t move.

After the sleep study, I was diagnosed with REM sleep behavior disorder.

As the sleep doctor explained to me, most people experience a temporary paralysis during rapid-eye movement (REM) sleep. That’s the stage of sleep where you do most of your dreaming on and off throughout the night. This is because your brain uses a nerve pathway to send a message to your muscles that basically says, “Hey! You’re sleeping and dreaming. This isn’t real life—so don’t move!” But that nerve pathway doesn’t work for people like me who have this disorder (also referred to as RBD).

As a result, we physically act out vivid, action-packed dreams. I was lucky in that my dreams were usually pretty pleasant. Unfortunately, many people living with RBD have super-scary dreams where they’re being chased or attacked. Often, they respond to them as you’d expect—by jumping out of bed, running, punching, or kicking. Ultimately, most people who have RBD end up seeking help for the same reason I did: because their sleep-acting has become dangerous.

While RBD might seem like an extreme version of sleepwalking, these sleep disorders take place during different sleep stages (sleepwalking happens during non-REM sleep) and the symptoms are different, too. One trademark of RBD is that if someone wakes you up mid-dream, you become lucid automatically and can remember what you’d just been dreaming about. Typically, that’s not the case for sleepwalkers.

REM sleep behavior disorder is really rare and only affects an estimated 0.5 to 1 percent of the population. And my case is even more of a rarity—RBD is a predominantly male disease and is typically diagnosed in men over 50 years old. But anyone—even young women!—can develop it.

While I was relieved to have a diagnosis, I was also really worried. To learn how to cope with RBD, I met with a sleep psychologist and psychiatrist. They prescribed me a medication called clonazepam (Klonopin), a common treatment for RBD that helped reduce my symptoms tremendously.

I also made some big lifestyle changes. To ease my anxiety, I started journaling, and I would imagine that I was putting my worries in a bag outside the door before I went to bed. I started practicing better sleep hygiene, too, like making sure I went to sleep and got up around the same time. To keep myself and my family safe, I installed special locks on my windows and doors and made sure to keep glass or any potential sleep-weapons out of my bedroom.

Since my diagnosis, I’ve learned that REM sleep behavior disorder is associated with neurodegenerative diseases, and I’m passionate about finding a cure for both.

People with RBD often (but not always!) develop neurodegenerative diseases like conditions like Parkinson’s disease, Lewy body dementia, and multiple system atrophy. Because of this, I see a sleep neurologist twice a year for a neurological exam, and so far, I haven’t had any concerning signs or symptoms.

Scientists believe that if we can learn more about the connection between RBD and these neurodegenerative diseases, we can potentially find better treatments for both. That’s why I’ve agreed to participate in multiple studies at the Washington University Sleep Medicine Center over the past few years.They call me the “research unicorn” because I’m not a man and I’m under the age of 50.

REM sleep behavior disorder is really rare and only affects an estimated 0.5 to 1 percent of the population.

I’ve also signed up to participate in upcoming studies with the North American Prodromal Synucleinopathy (NAPS) Consortium, a team of researchers at universities and institutions across the United States who are planning a clinical trial to test treatments to combat neurodegenerative diseases in patients with RBD.

Take it from me: If you’re having any trouble with sleep or dealing with other issues in your sleep, seek help because your sleep health is so important. A good night’s sleep not only helps our bodies rest, but it also helps store our memories and keep our brains healthy.

Before I received treatment for RBD, I used to have horrible treatment-resistant headaches every day. But after I started getting better sleep, they finally went away. I felt more rested. In general, I just felt better. I hadn’t realized how tired I’d been.

Source: Read Full Article