I made the doctor’s appointment simply to convince everyone I was fine. For the first half of 2012, my mom had been on my case about my decreasing weight and bizarre eating habits. She even brought up words no one else dared mention: anorexia relapse.

I laughed in her face. How could that be the case, I countered, when my weight was completely normal? I knew all about my past eating disorder (ED); I dealt with it during my late teens and 20s. But I had gained weight over the years due to normal life stuff—natural aging, medication—and my ED behaviors had subsided for chunks of time. So even though I had returned to some of the unhealthy food obsessions, like undereating and overexercising, that plagued my earlier years, I wasn’t particularly thin at this point, which made my recent weight loss less obvious. I can’t be in the midst of anorexia again, I told myself, and scheduled a standard checkup to prove it.

When the MD entered the room, we got straight down to business. I sat there in my paper gown as she reviewed my health history, which included my hospitalizations for ED several years earlier. “Anorexia, hmm?” the doc murmured, glancing up from the stack of papers to look me up and down. “Clearly, that’s not still a problem.” My cheeks flushed with shame even as I felt a twinge of satisfaction at hearing an expert confirm that my mom was wrong.

Except, of course, I did still have a problem. My hair was thin and I felt weak and light-headed when I stood up—residual effects, I told myself, of my history. Because the doctor never asked if I was still engaging in any ED behaviors, she took one look at my outward appearance and thought: Case closed. No longer at a low weight, I was fine…right? The next several years, during which I micromanaged calories and fretted over gaining, told a very different story.

Finally, when a relapse in 2018 left me near cardiac and kidney failure, I checked myself into an eating disorders hospital. There, I learned I was one among millions of people who fall into a diagnostic subcategory called atypical anorexia (which was added to the latest edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, a.k.a. the bible of psychiatry). Because we look bigger—we might even qualify as overweight on a medical chart—we’re often diagnosed later, because doctors don’t take us seriously. And despite being heavier, the problems we develop from anorexia—low pulse rate and low blood pressure, brittle bones, cardiac and kidney problems, even risk of early death—are just as severe. Yep, identical disorder, same complications, same challenges…but in a different group because our bodies send mixed messages.

“A name in the medical books means there are others like me—that I’m not the only one with this issue who doesn’t look the part.”

Historically, to get an official diagnosis of anorexia, you had to display harmful eating habits and also be clinically underweight. If you didn’t fit the stereotype of the disease, no label for you. As a society we’re conditioned to view anorexia through the lens of weight, says Lauren Muhlheim, PsyD, a therapist in Los Angeles who specializes in helping people navigate eating disorders.

“To call it ‘atypical’ is laughable,” says Jennifer Gaudiani, MD, a Denver-based physician specializing in eating disorders. Dr. Gaudiani adds that she’s seeing more people like me, who have physical signs of an ED (like hair loss and fatigue) but don’t fit the anorexia stereotype. And then there are the large number of folks who don’t seek medical attention for fear of facing weight bias—which is part of what kept me away from the doctor after that awful appointment in 2012.

Jamie Chung

Jamie Chung

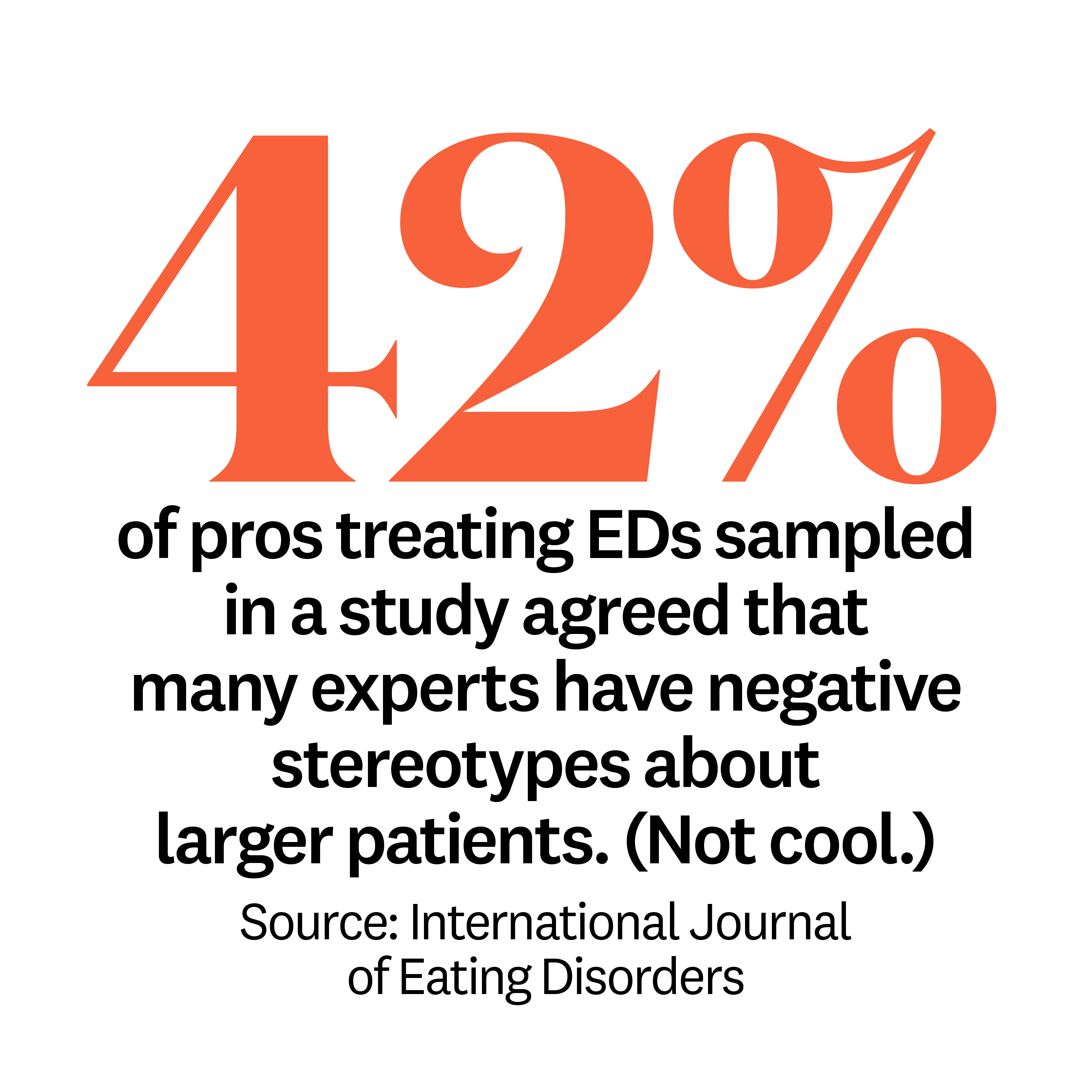

It can fill you with shame, even terror, to reveal a mental disorder like this to a medical professional when you don’t think you look sick enough. A therapist once tried to convince me I had binge-eating disorder because I was overweight. And back in my 20s, when I first got treatment and expressed hesitation about gaining, more than one provider assured me they wouldn’t “let me” get fat—as if fat were something to fear. Over and over, professionals reinforced stereotypes about EDs when they should have been challenging them.

I still consider myself one of the lucky ones, though. When I checked into the hospital two years ago, at 37, my husband and family rallied around me with unconditional support. I found a treatment center that understood me, and I spent five months there renourishing my body and learning new coping skills—like the Health at Every Size philosophy, a set of principles that taught me how to look after my well-being without pursuing weight loss. Now, I can finally see anorexia in a broader way. A name in the medical books means there are others like me—that I’m not the only one with this issue who doesn’t look the part.

I weigh more today than ever before. But I’m coming to terms with the fact that my size is only a tiny part of who I am. In fact, it plays no part at all when it comes to anorexia—and my health.

Think you or someone you know is experiencing an ED? Reach out to the National Eating Disorders Association hotline at 800-931-2237.

This article appears in the May 2020 issue of Women’s Health, available April 21. Subscribe now.

Source: Read Full Article