Wear a mask, keep your distance, avoid crowds—these are the common recommendations to contain the COVID-19 epidemic. However, the scientific foundations on which these recommendations are based are decades old and no longer reflect the current state of knowledge. To change this, several research groups from the field of fluid dynamics have now joined forces and developed a new, improved model of the propagation of infectious droplets. It has been shown that it makes sense to wear masks and maintain distances, but that this should not lull you into a false sense of security. Even with a mask, infectious droplets can be transmitted over several meters and remain in the air longer than previously thought.

TU Wien (Vienna), the University of Florida, the Sorbonne in Paris, Clarkson University (U.S.) and the MIT in Boston were involved in the research project. The new fluid dynamics model for infectious droplets was published in the International Journal of Multiphase Flow.

A new look on old data

“Our understanding of droplet propagation that has been accepted worldwide is based on measurements from the 1930s and 1940s,” says Prof. Alfredo Soldati from the Institute of Fluid Mechanics and Heat Transfer at TU Wien. “At that time, the measuring methods were not as good as today, we suspect that especially small droplets could not be measured reliably at that time.”

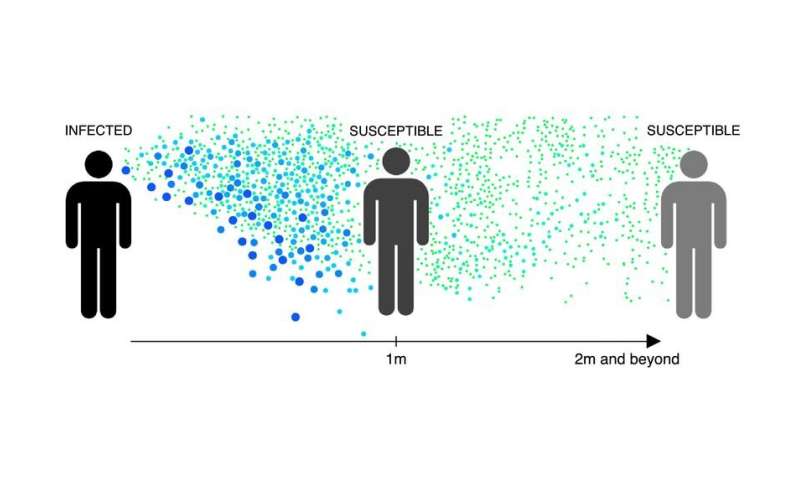

In previous models, a strict distinction was made between large and small droplets: The large droplets are pulled downwards by gravity, the small ones move forward almost in a straight line, but evaporate very quickly. “This picture is oversimplified,” says Alfredo Soldati. “Therefore, it is time to adapt the models to the latest research in order to better understand the propagation of COVID-19.”

From a fluid mechanics point of view, the situation is complicated—after all, we are dealing with a so-called multiphase flow: The particles themselves are liquid, but they move in a gas. It is precisely such multiphase phenomena that are Soldati’s specialty: “Small droplets were previously considered harmless, but this is clearly wrong,” explains Soldati. “Even when the water droplet has evaporated, an aerosol particle remains, which can contain the virus. This allows viruses to spread over distances of several meters and remain airborne for long time.”

In typical everyday situations, a particle with a diameter of 10 micrometers (the average size of emitted saliva droplets) takes almost 15 minutes to fall to the ground. So it is possible to come into contact with virus even when distancing rules are observed—for example in an elevator that was used by infected people shortly before. Particularly problematic are environments with high relative humidity, such as poorly ventilated meeting rooms. Special care is required in winter because the relative humidity is higher than in summer.

Protection rules: Useful, but not enough

Source: Read Full Article