The benefit of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination among people with a history of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection is uncertain. In a recent study published on the preprint server medRxiv*, researchers estimate the effectiveness of primary vaccination and a booster dose against the Omicron infection in people with and without prior SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Study: Effectiveness of Primary and Booster COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination against Infection Caused by the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variant in People with a Prior SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Image Credit: Kim Kuperkova / Shutterstock.com

Effectiveness of primary and booster vaccinations

COVID-19 vaccines provide immune protection against the Delta Variant. However, the extent to which vaccination protects against infection with the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant has been reported to be lower.

Primary vaccination constitutes two doses of the messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) vaccines, with the booster vaccination as the subsequent third dose of the vaccine. Several studies have shown that primary and booster vaccination reduces the risk of Omicron-related outcomes; however, the role of prior SARS-CoV-2 infection in vaccine effectiveness is not known.

Primary vaccination provides greater immune protection against reinfection as compared to the immune protection provided by prior infection. Moreover, a booster dose provides a boost to immune protection.

Notably, these conclusions were obtained from studies conducted prior to the Omicron wave. In fact, one study showed that primary vaccination did not provide additional immune protection against reinfection among individuals with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection during the first month of the Omicron wave.

Taken together, there remains limited information on whether booster vaccination provides additional immune protection against the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant in individuals with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection. Data in this regard would inform decisions concerning vaccination policies for these individuals.

About the study

Data collected from the Yale New Haven Health System (YNHH) was a part of the Studying COVID-19 Outcomes after the SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Vaccination (SUCCESS) Study.

The current study utilized a test-negative case-control study design, which provides effectiveness estimates that are comparable to those from randomized control trials. This type of study design is used to estimate the real-world effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines while also reducing the risk of wrong estimates due to care-seeking and testing access.

The Yale Computational Health Platform was used for demographic, comorbidity, COVID-19 vaccination, and SARS-CoV-2 testing data. The current study analyzed data from individuals who were tested for S-gene target failure (SGTF) with an outcome of Omicron infection. All data were stratified by prior SARS-CoV-2 infection status.

The effectiveness of primary vaccination was estimated during the period before booster eligibility, as defined as 14-149 days after primary vaccination, as well as during booster eligibility, which was greater than 150 days after primary vaccination. The likelihood of infection among boosted and booster-eligible individuals was compared.

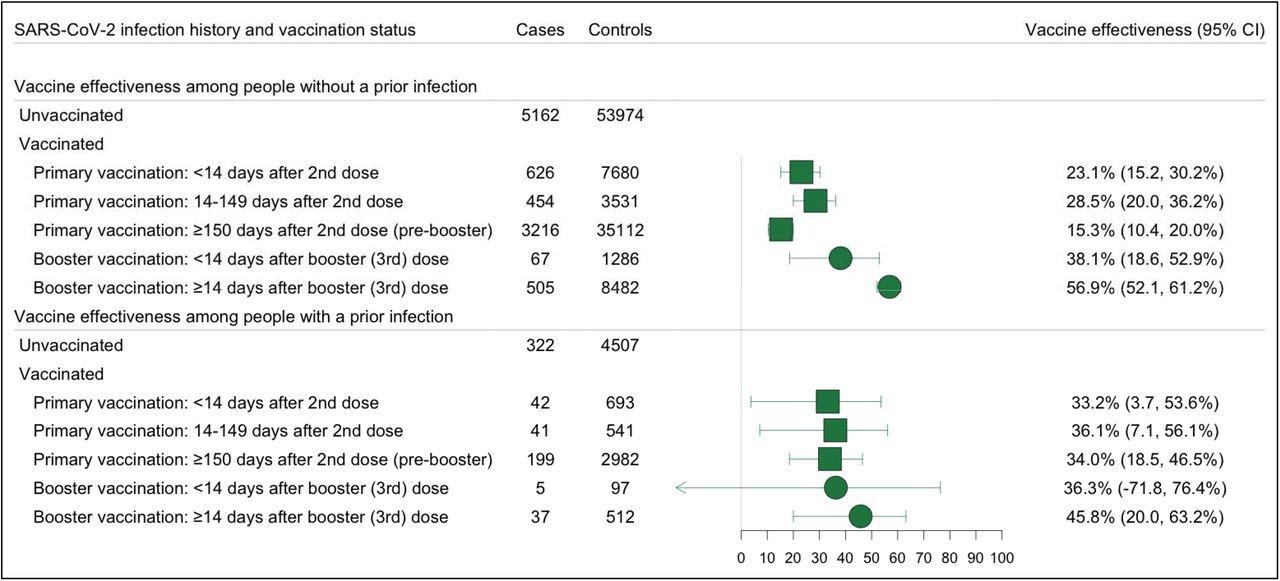

Effectiveness of Primary and Booster Vaccination with COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines Against SARS-COV-2 Omicron Variant Infections, Stratified by the History of a Prior SARS-CoV-2 Infection Forest plot depicting vaccine effectiveness against any Omicron and Delta infections for both US approved mRNA vaccines (BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273) among people with and without a prior infection. Prior infection was defined as a positive RT-PCR or rapid antigen test at least 90 days before testing. Omicron infection was defined as the presence of S-gene target failure (SGTF) defined as ORF1ab Ct < 30 and S-gene – ORF1ab >= 5, or ORF1ab < 30 and S-gene >= 40. Vaccine effectiveness was estimated as 1-OR from a model adjusted for date of test, age, sex, race/ethnicity, Charlson comorbidity score, number of non-emergent visits in the year prior to the vaccine rollout in Connecticut, insurance status, municipality, and social venerability index (SVI) of residential zip code in all analyses and time between testing and last prior infection in analyses of people with prior infection.

Vaccine effectiveness in individuals with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection

The current study identified 155,827 SARS-CoV-2 tests from 113,033 individuals between November 1, 2021, and January 31, 2022. Out of 138,349 eligible tests, 10,676 were Omicron infections (cases).

Of the 127,673 negative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests that were negative for COVID-19, three negative tests (controls) per person were selected randomly, which resulted in a total of 119,397 controls.

The mean age of the study population was 35 years for cases and 39 years for controls. In the study population, 6.1% of cases and 7.8% of controls had a prior SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The effectiveness of primary vaccination was 36.1% for individuals with prior infection and 28.5% for individuals without prior infection. The effectiveness of booster vaccination was 45.8% for individuals with prior infection and 56.9% for individuals without prior infection.

The likelihood of Omicron infection was similar for boosted and booster-eligible individuals with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection, with an odds ratio (OR) of 0.83. The likelihood of Omicron infection was lower for boosted than booster-eligible individuals without prior SARS-CoV-2 infection, with an OR of 0.51.

Limitations

The current study was limited to the Connecticut population with medical record data. The population mostly represents mild COVID-19 cases. Additionally, the study findings may be confounded due to residual behavioral differences.

The analyses did not test associations for severe COVID-19; therefore, the possibility that booster vaccination may increase protection against severe outcomes in people with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection cannot be excluded.

Conclusions

Primary vaccination provided significant but limited immune protection against Omicron infection among individuals with and without prior infection. Booster vaccination was associated with additional protection in people without prior infection. However, it was not associated with additional protection among people with prior infection.

Taken together, primary vaccination should be administered to people, irrespective of their prior infection status.

*Important notice

medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

- Lind, M., Robertson, A., Silva, J., et al. (2022) Effectiveness of Primary and Booster COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination against Infection Caused by the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variant in People with a Prior SARS-CoV-2 Infection. medRxiv, doi:10.1101/2022.04.19.22274056. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.04.19.22274056v1.

Posted in: Medical Science News | Medical Research News | Disease/Infection News

Tags: Coronavirus, Coronavirus Disease COVID-19, covid-19, Gene, Omicron, Polymerase, Polymerase Chain Reaction, Respiratory, Ribonucleic Acid, SARS, SARS-CoV-2, Severe Acute Respiratory, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, Syndrome, Transcription, Vaccine

Written by

Dr. Shital Sarah Ahaley

Dr. Shital Sarah Ahaley is a medical writer. She completed her Bachelor's and Master's degree in Microbiology at the University of Pune. She then completed her Ph.D. at the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru where she studied muscle development and muscle diseases. After her Ph.D., she worked at the Indian Institute of Science, Education, and Research, Pune as a post-doctoral fellow. She then acquired and executed an independent grant from the DBT-Wellcome Trust India Alliance as an Early Career Fellow. Her work focused on RNA binding proteins and Hedgehog signaling.

Source: Read Full Article